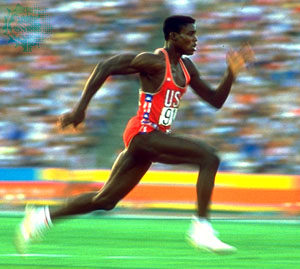

All elite athletes have a lot in common. That’s largely because many sports, when it comes down to it are all played on the same foundation of well-rounded athletic development. Power on the basketball court and power and on the soccer field are examples of how the same ability can be transferred in different ways. Whether it’s basketball, lacrosse, soccer, or ice hockey, wrestling, or track, many abilities are transferable across sports. Think about how prized speed is. How beneficial it is be able to change direction and accelerate quickly, or be able to withstand an opponent trying to take the ball from you. Speed, size, strength, quickness, and coordination are traits that are transferable to any sport. The development of these abilities are all built upon a strong foundation of sound movement patterns and mechanics. These movement patterns are the bedrock of any elite athlete’s overall development.

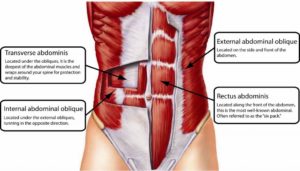

When an athlete can learn how to move, and move well, all other activities down the road become much easier. Proper squat and hinge patterns are the same movement patterns that make up a sprint. The aggressive hip flexion and knee flexion as the knee drives up in a sprint is the squat pattern, while the hip reaching full extension is like an athlete coming up out of a deadlift. Without the development of these motions in a controlled environment with attention devoted to proper technique, an athlete is missing a big piece of the puzzle. A well-designed and well-coached strength and conditioning program avoids and improves mobility restrictions and muscle imbalances. To give an example, consider a student-athlete who sits in class all day. Immediately after school, with their hips predisposed to a flexed position they go run at soccer or lacrosse practice. Since the front of their hips are tight, the extension comes from the lumbar spine when they run instead of the hips, a situation we’ve talked about previously. The next day, the athlete complains of low back soreness which leads to further, chronic, low back pain. However, if the athlete has learned how to engage the anterior core and the glutes properly through combination of abdominal, squat, and hinge movements, there’s no low back pain, because the glutes are activating the way they should. Furthermore, performance will be improved as a result of teaching the body to move in a way to that recruits the right muscles for the job.

So many young athletes today want to jump into training hard. They’re in the weight room “grinding out” reps, working their butt off. In the weight room, or in any athletic setting really, you have to earn the right to work hard. Yes, learning how to do all the basic movements correctly is boring (though we try to make it exciting), and it will take time. If you’re rushing this process and loading weight on before you’ve mastered the technique, you’re not only wasting your time, but you’re just increasing the likelihood of injury. This is where I think a lot of sports coaches miss the boat when it comes to their strength and conditioning programs. They push their athletes to work harder and harder, lift heavier and heavier, which only further facilitates poor movement patterns. If you’re a basketball coach, you wouldn’t encourage your players to take as many free throws as they can with poor mechanics. You fix the mechanics first, however long it takes. Don’t load dysfunction. Just as loading good movement patterns will multiply the benefits, loading dysfunction will multiply the detriments.

For those looking to learn directly from myself and my colleagues at Fit 2 Excel, join us for our 7-week summer athletic performance program at Mount Mansfield Union High School, South Burlington High School, or at our facility in Essex. Learn more about the program and sign up online at fit2excelvt.com

If you’re looking to learn more about these movements, and how we coach them to get the most out of our athletes, please feel free to get in touch with me at [email protected].